An English Major Who Knows Nothing About Business Starts a Book Coaching Business: Part 2

This is Part 2 of Author Accelerator CEO Jennie Nash’s series, How I Built My Book Coaching Business. Read Part 1 here.

If you enjoy today’s content, you can sign up for Jennie's weekly newsletter here.

In my last post, I said I was inundated with people wanting my help, and that was only technically true in my head. Several people who’d heard about me from Lisa Cron or Barbara Abercrombie approached me to ask for help writing books, but it felt like a flood because while I felt relatively confident in the process I had developed to guide a book writer, I had no systems or processes around pricing, scheduling, expenses, or invoicing, and no boundaries in place to protect my time. It was all very chaotic.

A large part of the problem was that I didn’t think of what I was doing as “real” business.

My husband had received his MBA from UCLA — it was why we were in Los Angeles in the first place — and he was working at Toyota’s national headquarters in finance. To me, that was what a real business looked like. It was big, it made big tangible things, it was filled with people who had economics and marketing and business degrees and talked about sales projections and supply chains and residual values.

I had friends who were working for banks, law firms, software companies, and hospitals — they were doing real business. I was just an English major who had never studied anything the real world seemed to value. I would come to understand that this was wildly inaccurate. English majors understand story, how to read a room, how to find meaning, why people do what they do, how to spot holes in a plot, how to think critically and logically, and how to write persuasively, which are all enormously important to running a business.

But at the time, I didn’t get any of that. I was just doing this thing where I helped writers, using a process that wasn’t exactly like the process of teaching in a classroom and wasn’t exactly like traditional editing, and didn’t even have a name so it was easy not to take it seriously.

In short, I was flying by the seat of my pants.

In addition to book coaching, I was also teaching, doing freelance magazine work, writing my third book, and fitting all of it into the hours my kids were in school, which in early grade school is not a very dependable timeframe. You never know when one of your kids is going to get an ear infection and have to stay home or when you will be invited to watch the Halloween parade.

Like I said: Seat. Of. My. Pants.

But here’s the thing about flying by the seat of your pants: it’s fun, and sometimes it works.

Most Writers Just Wing It, Too

Winging it is what the vast majority of writers do when they start writing a book. They catch an idea for a story or for something they want to teach or to say, and they start to write. They listen to the voice in their head, they carve out the time to put words on the page, and they GO.

That impulse to create, to take action, is powerful.

And sometimes the result is exactly what you want. Sometimes the writer sells the book or watches as it becomes a reader favorite. And sometimes the fledgling entrepreneur gets clients, delivers the outcome those clients desire, and makes money.

That is what happened to me — but I would learn that I was lucky, and that most of the writers who meet success that way are lucky, too. The vast majority of writers — and most book coaches — need to be more intentional about their goals if they have any hope of reaching them.

A Good Process Leads to Results

Among that small flood of people who came to me for help writing books was Sam Polk. He was burning to tell his story but he didn’t know what his story even was. He was a young man who had made a lot of money on Wall Street and realized it didn’t fix the holes in his heart.

I met him when he had written nothing — not one word. And he didn’t yet know what his book was going to be about. In fact, he didn’t even tell me the part about money and Wall Street for several months; he thought he was writing a book about being bullied — and he was. But that wasn’t all he was writing about.

I could tell because the material about being bullied felt flat. It was fine but it wasn’t why Sam was showing up to work with me every week, hungry to figure out how to write a book, and it wasn’t what was going to attract and engage a reader.

This is what I was beginning to learn: that knowing why a writer is motivated, and why they are so drawn to their material, is critical to helping them find their voice.

Trying to help Sam get to the root of his story and figure out what he was trying to say helped me refine my process and make it even better. It was where I began to codify what would become my Blueprint for a Book process — a series of 14 questions a writer asks themselves before they start to write, or when they get stuck, or when they are revising.

Why are you even doing this? Is Question 1.

It’s a process designed to clarify and to push the writer to go deeper. And it was such a thrill to see it work in real time.

Sam was committed and motivated. He had been a literature student at Columbia University and he knew what made a good story; he just didn’t know how to produce one.

When he finally figured it out, he flew through the writing of his book — a story that now just hummed with tension and despair and redemption — and then spent more than a year refining the manuscript and getting it just right. He pitched to 88 agents, landed one, and sold his memoir, For the Love of Money, to Scribner.

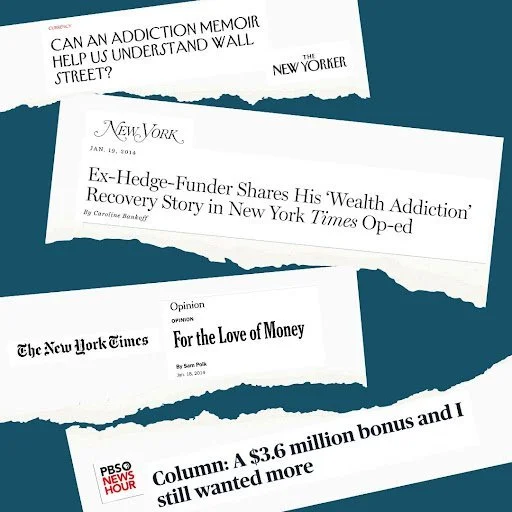

The book got a lot of attention on TV outlets and traditional media.

Sam’s book also became the origin story for his new life — a life in which he was dedicated to something other than a money grab. Not long after the book came out, he founded a company, called Everytable, that is bringing food equity to cities all over America.

Form Is Function

The next writer I coached was Tracy Tynan, the daughter of famous theater critic, Kenneth Tynan. She was a Hollywood costume designer who had worked on films like The Big Easy and Great Balls of Fire. Katherine Hepburn was her godmother and her parents were friends with people like Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh.

Tracy wanted to write about her zany childhood and what it is like to be surrounded by so much celebrity and so much reckless creativity, but she also wanted to write about clothes. A book like this can be deadly dull and self-indulgent: let me tell you about this thing that happened to me and this thing and this other thing.

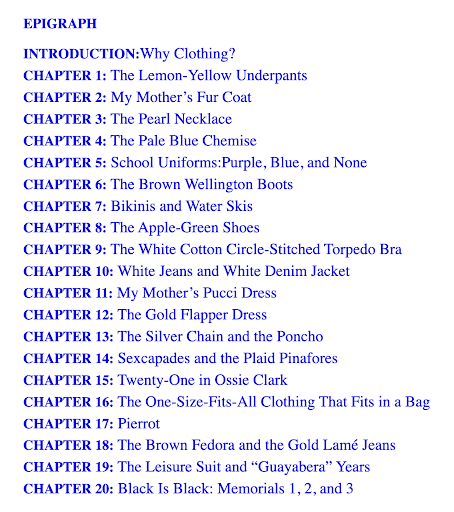

Tracy didn’t want to write a book like that — and I didn’t want her to, either. I used some of my new ideas to help Tracy define the point of her book (Step #2 of the Blueprint) and craft a powerful structure for telling her story (Steps # 8 through 12.). She landed on the idea of telling her story through clothes. Each chapter centers a piece of clothing, but also moves the story forward and propels the narrative.

It’s been years since I helped Tracy, and I can still remember many of the moments in her story because of the incredible descriptions — the apple-green shoes she was desperate to own — but also because she learned how to be vulnerable in her storytelling, and how pin emotion to the page.

This is what (part of) the final table of contents for her book, Wear and Tear: The Threads of My Life, looks like:

Wear and Tear was published by Scribner in 2016 and was a critical success. These were just some of the rave reviews. I share them to show what she accomplished in her book — it is so far from a “and then this happened” indulgence and is, in fact, a story made to help the reader understand an era, a family, and the power of making your own way in the world. Books that deliver rich experiences for the reader became the North Star I wanted for every writer I helped.

Inspiring Other People to Raise Their Voice Is Deeply Meaningful Work

Sam and Tracy’s books actually came out within a few months of each other, and when I went to hear Tracy read at Book Soup, a wonderful bookstore off Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood, both their books were on the front table.

I remember so clearly standing there and seeing those books and thinking, This is freaking amazing.

I was filled with a sense of pride and accomplishment and joy and purpose and I knew that I had found the work I was meant to do.

My girls were getting older and more self-reliant, I was still teaching and writing my own books — I’d sold a novel about a breast cancer survivor in a two-book deal to Penguin — but there was something about book coaching that felt important to me. People continued to want me to help them do it — referrals from Lisa and Sam and Tracy, and people connected to UCLA who had heard of my book coaching success.

I began to realize that book coaching allowed me to draw more of my talents than writing did. It put me in creative conversation with people. Rather than working alone in a room, I was working with other people to see the story, get it on the page, and figure out how it might fit in the marketplace.

I loved it.

But I was spending a great deal of time doing it and not making very much money, so in order to keep doing it, I had to pay attention to the business aspects I had so smugly ignored.

Bad Money Habits Lead to a Dysfunctional Business Relationship

There is a tradition in freelance editing to charge by the word or the page — a few pennies per word, a few dollars per page.

I was working as a freelance writer, and it was the same system with magazine work: $1/word was the top end of the pay scale. For a 1,000-word piece, you would make $1,000.

I had very quickly understood that what I was doing with my writers was not the same thing as editing. So much of the work was not “on the page.” Sometimes I was reading and editing pages, but other times I was searching bookstores for competitive titles for my clients' books. Sometimes I was reading articles or books they sent me off to read or meeting with them in a coffee shop. Sometimes I was designing exercises for them to do to get to their WHY, asking them to revise pages, or talking to them on the phone about their doubts and fears and desires. (There was no Zoom — there wasn’t even texting. I think I had a flip phone.)

So instead of charging by the word or page, I charged by the hour. I don’t remember exactly what rate I started at, but it was definitely less than $50 an hour because I remember when I raised my rate to $50 an hour thinking this fee was preposterous — like I was getting away with something.

I dreaded telling people how much I charged. I skirted around the issue for as long as I could. I usually did a bunch of free work for them while they were debating whether or not they wanted to go all in on their project. I would send invoices late, or sometimes not at all. I once had a client remind me that I hadn’t asked for a fee.

I did not track my time; I usually low-balled the number of hours I spent, based on the time I spent actually editing or on the phone.

I had a hundred bad habits around money, and I was not making very much of it, despite the fact that I kept getting clients, and they kept achieving amazing outcomes.

In 2011, the third year I was doing it, I made $39,000 from my part-time book coaching. This was more than I made from any of my traditionally-published books.

But I began to resent my business. I was giving my writers so much, and helping them so much, and I was scrambling to meet deadlines and make everyone happy, and that resentment led me one day to say, “Screw it, I’m charging $120/hour!”

I thought raising my rates was the answer.

In 2013, I cracked six figures and made $122,000 from book coaching. I felt like I was entering the big leagues, but the truth was that the per-hour rate was still a very minor league move. I wasn’t anywhere close to the arena I would one day play in.

And I had not yet begun to understand the dysfunctional relationship I had with my business — a concept I would later learn about from thinkers like Nicole Lewis-Keeber and Tara McMullin, among others. I was measuring money and not joy or ease or purpose; I was devaluing my worth; I was handing over my power to my clients by letting them tell me what they wanted, and how things would go, and negotiating a new plan and process and price every single time someone started working with me.

Next week I’ll write about how I got out of the per-hour pay trap, which was the gateway to a much better business in every way.